Give Me Some of That Old Time Description

|

The sunset was like a bright beam of orange spun cotton

candy dancing on a fiery mound of... oh screw it.

|

So description.... yeah...

Even though I draw, my writing has always been weakest when I try to describe things. Objects in a room. A sunset. Clothing. Faces.

Still, I didn't think that my description was that bad until I encountered the view that historical novels should immerse you in the period, fully fleshing out the world to make you feel as if you were there. See, for example, The Crimson Petal and the White.

I don't immerse. I describe and move on. Now and then, I'll mention a detail if I think it's important. Or I might give a thorough description of a character if that character matters. But I don't linger. I rarely paint a scene.

I never thought that lessened my readers' enjoyment, but maybe I've been depriving them. Maybe I should take the time to really sketch out the surroundings. After all, it's not as if they all know as much about the Victorian period as I do. Why take for granted that they could just visualize?

In mulling it over, I realized that I have several reasons that go beyond simply "weak at description." They suggest the difficulty of finding a middle ground between not enough description and too much.

1. Get the Scene Moving!

One thing I've learned from both script and fiction writing is that to keep the reader's attention, you need to get the scene moving and now! You need to start the scene as late as you can -- no time spent lolly gagging and setting things up. And once you have the characters in conversation, don't slow it down by constantly describing characters' movements.

Such directives tend to discourage scene painting. I don't mind, truth be told. That's because when I write, I have an orchestra playing inside my head, telling me when and how to lay down the beats to the music. Pausing to toss out details like the way a character's hair falls on her head -- again, unless relevant -- just slows me down and takes me out of the scene.

2. Seeing the Scene Through Your Character's Eyes.

Another issue, which is specific to my current novel, is that I am uncomfortable describing things that my characters would not have noticed or cared about. It's an issue that, say, The Crimson Petal and the White manages to avoid by having an all-knowing tour guide narrator from the future. Such a narrator is only too happy to describe everything down to the door knockers because he knows that we modern viewers have no idea what they're like (well okay, door knockers).

In my case, Rage and Regret is written in close third-person perspective, which is about as close to first person as one can get without being it. Each chapter is told from a specific character's point of view. The narrator is not omniscient, but rather he or she (it?) knows only as much as the character. Therefore, it wouldn't be realistic for the narrator to describe things that the character is already familiar with or wouldn't notice.

So while I would describe the setting as "one of those adorable, quaint towns where everything is made of crumbling yellow stone and the roads are super cute and narrow,"* obviously no character would. They wouldn't think it was quaint; more likely, they would find it backward. They would see other things that my eye would gloss over -- defects, embarrassments, inconveniences. Instead of noting the details of a town they have known their whole lives, they would note the weather. That makes it a challenge to write vivid description.

By contrast, in my next novel, the main character will be in a setting that is largely foreign to her. Setting details will be important then, because it will tie in with what the character is feeling, and what options are available to her.

* And yes, that is a terrible description that would never find its way into any of my books.

3. Other Books From That Genre Don't Have Immersive Descriptions.

If my descriptions aren't immersive, it may be because many of my favorite authors aren't immersive, either. Writers from the 19th century, in particular, seemed content to just give an initial description and move on, trusting that readers will remember. There aren't minute descriptions of dung or street mud or the characters' chin hair every other page. At least, not the authors I read -- Eliot, Trollope, Austen.

Ah yes, Jane Austen. Even though she is not a Victorian author, she practically pioneered the country house genre. Yet while she is famous for her clever wordplay, her descriptions are not, shall we say, memorable. Take the moment where Elizabeth first sees Pemberley in Pride and Prejudice:

"Elizabeth's mind was too full of conversation, but she saw and admired every remarkable spot and point of view. They gradually ascended for half a mile, and then found themselves at the top of a considerable eminence, where the wood ceased, and the eye was instantly caught by Pemberley House, situated on the opposite side of a valley, into which the road, with some abruptness, wound. It was a large, handsome, stone building, standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high woody hills; -- and in front, a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. Its banks were neither formal, nor falsely adorned." (Pride and Prejudice, Chapter I, Volume III)

A "large, handsome, stone building"? A fairly adequate description. Then we get to the interior. "They followed her into the dining-parlour. It was a large, well-proportioned room, handsomely fitted up." Also: "The rooms were lofty and handsome, and their furniture suitable to the fortune of their proprietor; but Elizabeth saw, with admiration of his taste, that it was neither gaudy nor uselessly fine; with less of splendor, and more real elegance, than the furniture of Rosings."

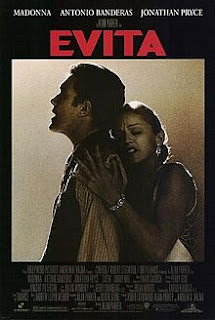

Not bad, you say? Well here's what Pemberley looks like:

Does Austen's description come close to doing it justice? When you read "large, handsome, stone building" and about "lofty and handsome" rooms, is this what springs to mind? Admittedly, both film productions of Pride and Prejudice took some liberties with Pemberley. Yet an "immersionist" would argue that Austen should have provided a much clearer description -- so that we could feel its intimidating grandeur, see the mold on the ancient greying stones, smell the dank smells, feel the drafts.

There is nothing wrong with wanting those things. But do they help the scene? Do they help convey what Austen was trying to convey? Moreover, without them, is the scene flatter? Do we feel less interest in Pemberley, or Elizabeth's views of Pemberley?

If readers are all the poorer for Austen's description, it is not apparent. Millions delight in Austen's language when it comes to Pemberley and everything else. This despite the fact that current readers would not be familiar with the sights that Austen describes. (Even in Austen's day, I doubt many had the time and money to tour great houses.) In my opinion, Austen was never interested in describing every candlestick in the building; she wanted to convey Elizabeth's growing infatuation with Pemberley, which led to her change of feeling toward Mr. Darcy.

4. A Lot of Description = Over the Top

Finally, I have never favored a lot of description because it is so easy to go too far. A few poorly chosen words and a description goes from sensuous to ridiculous. So many times I read descriptions that try so hard to break apart an image and rebuild it into something new that they make no sense whatsoever. Sometimes a sunset is just a sunset.

That Said, Should Historical Fiction Attempt to Immerse Readers?

It's a good question. I think every author of historical fiction should try to make the setting clear and accessible -- especially those writing about lesser-known settings. But the amount of scenery description should depend on what you are going for: if you want a taut novel that readers can burn through in a few hours, you don't need a lot. If you want a luxurious novel where readers wallow in the surroundings, you do. If you want a character-driven novel with a good plot, you might want something in between.

If there is one thing I'm finding, it's that you can have a slim novel (under 100,000 words), a novel with great characters and plot, and a novel with evocative scenery -- but not all three. You simply can't fit them all in. There is a reason The Crimson Petal and the White was 850-plus pages, and even then it didn't have enough plot. Others may argue with this assessment, and I'd certainly be open to hearing about exceptions. But in my opinion, since you can't have all three, you have to ask yourself which is most important.

I want to improve my scenery description, but it will probably always take a back seat to plot and character. When I get to write big, long books, I will try to include all three. Otherwise, my readers will just have to rely on their imaginations a bit more.

The top image was free to use, while the Austen film photos were used under the Fair Use Doctrine.

Comments

Post a Comment