Book Review: The Crimson Petal and the White

This will shock you: when I sat down to write my neo-Victorian novel, I was not exactly aware of the current market for my genre. I simply reasoned that if people still liked books written 150 years ago, they would be just as happy to read a more modern take.

Turns out that knowing your market is pretty important. One reason is because when you write a query letter, it is often ideal to suggest that your book resembles Book X, which was written in the past 10 to 15 years and sold bazillions of copies. I did some Google searches, but the neo-Victorian market was surprisingly sparse -- most well-known books like The French Lieutenant's Woman had been written decades ago.

So I went onto Victorian listserv and asked for some examples of popular recent Victorian novels. One of the examples mentioned was Michel Faber's The Crimson Petal and the White (2002). Since that seems to be the most popular recent example, that is where I will start.

My purpose in reviewing books like Crimson is this: (1) to note what aspects of the Victorian Era they incorporate; (2) to see what "modern" elements they bring; (3) to see what works and what does not work; (4) to see how well it conforms to expectations of "what will sell"; and (5) whether it's a good story. And most importantly, tying into No. 5: why was it successful?

Background

I will just say right off: The Crimson Petal and the White breaks all of the rules. Breaks them? No, it laughs at them, sticks out its tongue, and says "Neener, neener!"

At 850 or 950 pages, the novel far exceeds the preferred 100,000-word length for historical fiction. It ignores the needs of editors and publishers for slim novels that aren't a monster to shape or too expensive to produce. Perhaps that's because while Crimson was the first novel Michel Faber wrote, it was not the first book he published. The Dutch-born Scotland resident first published a book of short stories, Some Rain Must Fall (1998), then a much-slimmer novel, Under the Skin (2000), which won him critical acclaim.

Therefore, Faber had a bit more flexibility to debut his enormous second novel, which apparently took two decades and 85 historical experts to bring to fruition.*

That said, is it a good book? I thought so, for the most part. It had some wonderful aspects and some really problematic ones. Many people criticized the ending, but to me, that was less of a problem than the story structure that brought us to that point. Overall, I would call it highly readable, but flawed.

One Goodreads poster characterized Crimson as an "almost bad" book, stating that "almost bad" was worse than "bad" because "almost bad" teased you with the possibility of being excellent, before letting you down. For me, it's the reverse: Crimson is "almost excellent," which is better than an excellent book. Excellent books tend to be praised and forgotten, while almost-excellent books leave a reader forever thinking about them, pondering alternate scenarios that would have elevated them and their characters. That's what The Crimson Petal and the White does to me.

Plot Synopsis

Before you go any further, keep your wits about you, for I shall be disclosing spoilers. Other reviewers treated you like a friend, made you believe that you belonged, that you could read their impressions without learning major plot details. Only now do you realize that you are not on Amazon, where reviews fade from memory the moment after you read them, and reviewers are too hurried to leave their full impressions. You fear that it's too late to turn back.

The novel is set in London, from 1874 through 1875. It revolves around a teenage prostitute named Sugar, who works in a brothel run by her mother, Mrs. Castaway. Due to Sugar's unusual intellect and willingness to do anything a male customer asks, she draws the attention of William Rackham, reluctant heir to a successful perfume business.

William becomes so enthralled by Sugar that he decides that he wants her only for himself. To that end, he vows to master the business and become a success in order to make Sugar his kept woman. Initially thrilled with her freedom from Mrs. Castaway's brothel, Sugar comes to find her life tedious and fears that William will eventually lose interest in her. She therefore convinces William to take her into his household as a governess to his young daughter, Sophie. There, Sugar becomes intrigued by William's wife, Agnes, even secretly reading diaries that Agnes had discarded.

In a separate subplot, William's brother, Henry, wants to become a clergyman, but doubts his fitness after he experiences lust for his friend, social reformer Emmeline Fox.

As Sugar draws closer to Sophie, she and William grow further apart. The true break occurs after the unstable Agnes disappears and is presumed dead. William eventually terminates Sugar's employment, and Sugar responds by kidnapping Sophie and taking her on a long journey to an undisclosed location. William rushes out to look for them, but finds nothing.

The Good Aspects of This Novel

The strengths of The Crimson Petal and the White lie in Michel Faber's use of language, his ability to create vivid imagery and memorable characters.

Language. The imagery leaps out at you right away. In another example of rule breaking, Faber does not begin with first person or third person, but second person. "Keep your wits about you; you will need them," the unnamed narrator insists, before the reader is assaulted by "icy wind," sleet "like fiery cinders," and "smells of sour spirits and slowly dissolving dung."

Faber uses this painterly approach with all of his scene setting. The result is that the reader feels fully immersed, able to see and smell everything present -- for better or worse. You not only get to experience the luxury of a dinner party during the "season," but also a gruesome ritual where prostitutes use a caustic douche to scrub themselves free of semen in an effort to avoid pregnancy.

Historical Detail. Such detail would not be possible without Faber's research into the period. Billed as the novel Dickens would write if he weren't constrained by Victorian mores, Crimson benefits from Faber's access to materials on the real lives of prostitutes during that era. The research appears quite solid for the most part, only occasionally showing cracks (would upper-class ladies have really attended funerals back then?). If at times Faber's use of it feels a little too showy, its overall effect is to create a vivid, wholly authentic portrait of life in the mid-1870s.

Characters. In addition to scene setting, Faber knows how to sketch out interesting characters. First there is Sugar, described as having an almost masculine body and a skin condition; yet there is some elusive quality that makes her more irresistible than conventionally pretty women. She inhales all kinds of reading materials, and is therefore better spoken than many of her fellow prostitutes. In her spare time, she writes a violent novel that aims to tell the "true story" of a prostitute's life.

It takes a while before the reader gets Sugar's uninterrupted point of view (a problem that I will touch upon later), but once you do, it is hard to put Crimson down. For the most part, her evolution from cynical prostitute to properish lady is convincing. However, what struck me as truly excellent was the way Faber wove instances of Sugar's past abuse into the narrative. There is no specific scene of Sugar's mother being evil; instead, brief moments of her cruelty are scattered throughout the novel's second half, forming a disturbing whole.

William Rackham is similarly painted in detail -- his hair alone could be a separate character. Likewise, Agnes is given depth due to her strong Catholic faith, despite being the novel's "mad wife in the attic."

Even more minor characters get their due. Emmeline Fox is such a strikingly original woman that she could drive her own subplot or even her own novel. As for Henry, the reader learns almost too much about his beliefs and the depths of his inner pain.

The overall effect is that you care about these characters, or if you don't care, you are at least curious to find out how their lives end up. Which is why, no doubt, so many readers were outraged that The Crimson Petal and the White ended where it did.

The Problematic Aspects of This Novel

Characterization and vivid imagery allow the novel to overcome its shortcomings, which are mainly structural and plot based.

Structure. Just as Crimson grabs you instantly with its strong imagery, it also presents a problem: its structure is just odd.

The novel begins in second person, with the narrator acting as a bustling tour guide -- "Go here! Don't go here! Follow this person!" -- before settling into third person the rest of the way. The narrator informs you that you need the "right connections" to meet the main characters, before introducing you to the first character: Caroline, a prostitute on Church Street. Faber provides a vivid account of where she lives, where she sleeps, what she eats, and the life that led her to prostitution, leading the reader to conclude that if she is not the main character, she is at least an important supporting character. Then she meets Sugar and... goodbye, Caroline: you will hardly appear again.

If this were Les Miserables with a cast of thousands, this might not be so problematic. But just six characters take up most of the epic length, some of whom I liked far less than Caroline. Furthermore, it seems odd that Faber devotes so many pages to the horrors and degradations of Church Street when Sugar no longer lives there. At least now that Sugar has appeared, the reader will learn about her home life and be introduced to William Rackham, right?

Wrong. Just as the reader has Sugar alone, she idly passes by a carriage, and all at once, the narrative switches to William's perspective. So much for making the "right" connections for a proper introduction.

The effect is that Sugar remains mostly at arm's length for the first third of the novel -- which, given its heft, is quite a while. Maybe Faber wanted to deliver her appearances in tantalizing bits and pieces, but for me, it made that first third a tough read. A few pages of Sugar stuck between innumerable pages of Henry and Agnes.

These structural issues persist even after the first third. Faber often seems to be writing in free form, tossing out a scene because he feels like it rather than because it makes sense or builds momentum. The tour guide narrator pops up now and then, but is mostly absent until the end of the novel. Perspectives shift at random, turning characters whose thoughts you knew intimately into mysteries.

Plot. Then there is the novel's plot problem -- namely, Sugar's storyline is the only one to progress. With Agnes, it first seems as though she will have a good story arc involving struggles to overcome her ailment; but soon, Faber makes it quite clear that she will never improve. So despite some progress here and there, she mostly lapses into illness or is doped up in bed.

Yet that is substantial movement compared to Henry's subplot. Henry wants to be a clergyman, but he can't because he is in love and lust with Emmeline Fox, and at some point, they changed the rules and said that Anglican parsons couldn't marry? And he is so, so tortured about it!

Henry's dilemma would have made more sense if the Rackhams were Catholic. As it stands, a good subplot could have been carved out in which Henry finally admitted his love to Emmeline, or Henry helped Caroline, or Caroline helped Henry. Instead, Henry's subplot ends in an abrupt, crude manner without any growth or resolution.

As for Emmeline -- an intelligent, eccentric, yet respectable woman who reforms prostitutes -- she seems destined to play a major role in Sugar's storyline. Instead, she does not meet Sugar until near the end, being otherwise suspended in Henry's plot.

It is hardly a coincidence that once Henry and Agnes's chapters cease, the novel's pace picks up considerably.

Characterization. While Faber's characterization is strong enough to make you feel that certain characters deserved better, it is not without some significant holes.

The biggest of them involve William's character. William begins the novel a sad-sack, yet fun-loving fop with no head for business. Then, in less than six months, he evolves into a heavyset man consumed by business above all else. While in the first third of the novel, the reader gets his thoughts almost uninterrupted, by the end, the narrative has shifted to Sugar's point of view and William's actions are largely a mystery.

Does he love Sugar? Does he love Agnes? Why does he insist on making Agnes believe that Sophie does not exist? Would Agnes be that much worse off knowing she has a child? Does William start avoiding Sugar because he realizes that she can never take Agnes's place, or because he can't get an erection?

Sugar herself is not free of character issues. In the beginning, it is tough to feel anything for her because not only is she at arm's length, but she seems cynical and hard. Faber missed an opportunity by not sketching out her home life sooner. Among other things, he might have explained how she became so much more learned and cultured than the other prostitutes -- enough that she alone speaks English with a "proper" accent. Was it Mrs. Castaway's influence, or did she just feel like stealing library books one day?

Once Sugar moves out of Mrs. Castaway's brothel, her character and motivations become easier to understand. Even so, some of her actions draw question marks. She becomes fearful that William will start to forget her, so her answer is... to make herself available to him all the time? Because if there's one thing men hate, it's a challenge?

If Sugar were as savvy as suggested, you'd think she would realize that with people like William, less is more. If she wants him to desire her as madly as he did in the beginning, she should try to make herself less available. Instead, Sugar decides that the next step is to go from being a perfume-scented, well-dressed kept woman in a grand suite to... a dowdy governess in a cramped room upstairs.

Sugar does it in order to become indispensable to William, because at his side, there would be no limit to what she could do. But she seems to have not considered the implications of becoming William's servant. Moreover, "at his side" in what way? Most likely by becoming Mrs. Rackham after Agnes dies, but Faber never has her state it, as if fearing that it would make her less sympathetic.

So instead of a storyline where Sugar yearns to be Mrs. Rackham, only to change her mind once she gets to know Agnes, Faber has it so Sugar's ambitions are vague, and her main desires seem to be keeping William interested and learning about Agnes through her diaries (which turns out to be nothing we didn't already know). It's as if Faber had an earlier draft where Sugar had more defined ambitions, but changed it after someone complained that Sugar "wasn't very nice."

Maybe Faber would claim that he left things vague on purpose, to make the reader feel like a john who did not get everything he hoped for. But then why devote 800-plus pages to the characters at all, including multiple scenes where the same situations play out over and over? It is fine to leave some things about the characters unexpressed, but there should at least be some sense of a plan, even if that plan is very carefully hidden. Too often, it is unclear what the greater scheme is, or why characters behave the way they do.

Overall. So while Faber creates a world filled with undeniably rich sights, sounds, smells, and characters, it left me wanting. I can only imagine how much better The Crimson Petal and the White would have been if Henry and Agnes had real character arcs, or if Emmeline or Caroline were given more pivotal roles. Again, the tragedy isn't that the novel ends so abruptly, but that it wasn't better structured throughout.

Why Is the Novel Successful?

One reason for Crimson's popularity is that so many people were absorbed in the characters' lives. And while I may not feel like buying Sugar a Christmas present, I can certainly see the appeal.

That said, I suspect the novel would not have received nearly as much attention if not for one thing: Teh Sexx.

Descriptions of foreplay and sex abound in Crimson, many of them equal parts fascinating and gruesome. Nipples get twisted; semen glistens on pubic hair; one character's penis gets a rather luxurious bath. The descriptions of the consequences of sex are also there, from the prostitutes' douches to one chemical mix used to induce a miscarriage that is so horrifying, I have trouble buying that the character who used it walked away as easily as she did. (Part of me believes that after her miscarriage, she bled so heavily that she was taken to nearby St. Thomas's Hospital for a hysterectomy, and that the rest of the novel's events were part of her fever dream.)

While the novel has enough to recommend it, its status as "the book Dickens was too prudish to write" must have surely piqued countless people's interests. Come for the sex, stay for the character development. Though it worked in this case, I'm not sure it's a model that other neo-Victorian authors could follow.

That said, good characters and an intriguing premise are the only two things about Crimson that conform to the "what will sell" specifications. Otherwise, the novel thumbs its nose at conventions old and new, and is probably all the better for it.

Conclusion

So while The Crimson Petal and the White is not flawless, it is still highly readable and enjoyable. Apart from some basic elements, it is also a very different novel from my own. Well okay, in both novels, a main character has sex with prostitutes, so there's that.

Crimson is a worthy addition to the neo-Victorian genre, and if Faber ever writes the sequel that fans have clamored for, I will be among the first to order it.**

* Go read the Acknowledgements in the back if you think I'm joking.

** The Apple (2006) answers some questions, but not all.

Turns out that knowing your market is pretty important. One reason is because when you write a query letter, it is often ideal to suggest that your book resembles Book X, which was written in the past 10 to 15 years and sold bazillions of copies. I did some Google searches, but the neo-Victorian market was surprisingly sparse -- most well-known books like The French Lieutenant's Woman had been written decades ago.

So I went onto Victorian listserv and asked for some examples of popular recent Victorian novels. One of the examples mentioned was Michel Faber's The Crimson Petal and the White (2002). Since that seems to be the most popular recent example, that is where I will start.

My purpose in reviewing books like Crimson is this: (1) to note what aspects of the Victorian Era they incorporate; (2) to see what "modern" elements they bring; (3) to see what works and what does not work; (4) to see how well it conforms to expectations of "what will sell"; and (5) whether it's a good story. And most importantly, tying into No. 5: why was it successful?

Background

I will just say right off: The Crimson Petal and the White breaks all of the rules. Breaks them? No, it laughs at them, sticks out its tongue, and says "Neener, neener!"

At 850 or 950 pages, the novel far exceeds the preferred 100,000-word length for historical fiction. It ignores the needs of editors and publishers for slim novels that aren't a monster to shape or too expensive to produce. Perhaps that's because while Crimson was the first novel Michel Faber wrote, it was not the first book he published. The Dutch-born Scotland resident first published a book of short stories, Some Rain Must Fall (1998), then a much-slimmer novel, Under the Skin (2000), which won him critical acclaim.

Therefore, Faber had a bit more flexibility to debut his enormous second novel, which apparently took two decades and 85 historical experts to bring to fruition.*

That said, is it a good book? I thought so, for the most part. It had some wonderful aspects and some really problematic ones. Many people criticized the ending, but to me, that was less of a problem than the story structure that brought us to that point. Overall, I would call it highly readable, but flawed.

One Goodreads poster characterized Crimson as an "almost bad" book, stating that "almost bad" was worse than "bad" because "almost bad" teased you with the possibility of being excellent, before letting you down. For me, it's the reverse: Crimson is "almost excellent," which is better than an excellent book. Excellent books tend to be praised and forgotten, while almost-excellent books leave a reader forever thinking about them, pondering alternate scenarios that would have elevated them and their characters. That's what The Crimson Petal and the White does to me.

Plot Synopsis

Before you go any further, keep your wits about you, for I shall be disclosing spoilers. Other reviewers treated you like a friend, made you believe that you belonged, that you could read their impressions without learning major plot details. Only now do you realize that you are not on Amazon, where reviews fade from memory the moment after you read them, and reviewers are too hurried to leave their full impressions. You fear that it's too late to turn back.

The novel is set in London, from 1874 through 1875. It revolves around a teenage prostitute named Sugar, who works in a brothel run by her mother, Mrs. Castaway. Due to Sugar's unusual intellect and willingness to do anything a male customer asks, she draws the attention of William Rackham, reluctant heir to a successful perfume business.

William becomes so enthralled by Sugar that he decides that he wants her only for himself. To that end, he vows to master the business and become a success in order to make Sugar his kept woman. Initially thrilled with her freedom from Mrs. Castaway's brothel, Sugar comes to find her life tedious and fears that William will eventually lose interest in her. She therefore convinces William to take her into his household as a governess to his young daughter, Sophie. There, Sugar becomes intrigued by William's wife, Agnes, even secretly reading diaries that Agnes had discarded.

In a separate subplot, William's brother, Henry, wants to become a clergyman, but doubts his fitness after he experiences lust for his friend, social reformer Emmeline Fox.

As Sugar draws closer to Sophie, she and William grow further apart. The true break occurs after the unstable Agnes disappears and is presumed dead. William eventually terminates Sugar's employment, and Sugar responds by kidnapping Sophie and taking her on a long journey to an undisclosed location. William rushes out to look for them, but finds nothing.

The Good Aspects of This Novel

The strengths of The Crimson Petal and the White lie in Michel Faber's use of language, his ability to create vivid imagery and memorable characters.

Language. The imagery leaps out at you right away. In another example of rule breaking, Faber does not begin with first person or third person, but second person. "Keep your wits about you; you will need them," the unnamed narrator insists, before the reader is assaulted by "icy wind," sleet "like fiery cinders," and "smells of sour spirits and slowly dissolving dung."

Faber uses this painterly approach with all of his scene setting. The result is that the reader feels fully immersed, able to see and smell everything present -- for better or worse. You not only get to experience the luxury of a dinner party during the "season," but also a gruesome ritual where prostitutes use a caustic douche to scrub themselves free of semen in an effort to avoid pregnancy.

Historical Detail. Such detail would not be possible without Faber's research into the period. Billed as the novel Dickens would write if he weren't constrained by Victorian mores, Crimson benefits from Faber's access to materials on the real lives of prostitutes during that era. The research appears quite solid for the most part, only occasionally showing cracks (would upper-class ladies have really attended funerals back then?). If at times Faber's use of it feels a little too showy, its overall effect is to create a vivid, wholly authentic portrait of life in the mid-1870s.

Characters. In addition to scene setting, Faber knows how to sketch out interesting characters. First there is Sugar, described as having an almost masculine body and a skin condition; yet there is some elusive quality that makes her more irresistible than conventionally pretty women. She inhales all kinds of reading materials, and is therefore better spoken than many of her fellow prostitutes. In her spare time, she writes a violent novel that aims to tell the "true story" of a prostitute's life.

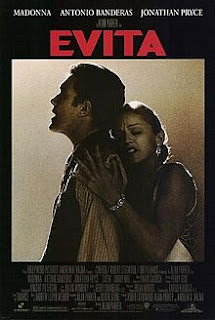

|

Gillian Anderson as Mrs. Castaway. Not really how I

pictured her.

|

William Rackham is similarly painted in detail -- his hair alone could be a separate character. Likewise, Agnes is given depth due to her strong Catholic faith, despite being the novel's "mad wife in the attic."

Even more minor characters get their due. Emmeline Fox is such a strikingly original woman that she could drive her own subplot or even her own novel. As for Henry, the reader learns almost too much about his beliefs and the depths of his inner pain.

The overall effect is that you care about these characters, or if you don't care, you are at least curious to find out how their lives end up. Which is why, no doubt, so many readers were outraged that The Crimson Petal and the White ended where it did.

The Problematic Aspects of This Novel

Characterization and vivid imagery allow the novel to overcome its shortcomings, which are mainly structural and plot based.

Structure. Just as Crimson grabs you instantly with its strong imagery, it also presents a problem: its structure is just odd.

The novel begins in second person, with the narrator acting as a bustling tour guide -- "Go here! Don't go here! Follow this person!" -- before settling into third person the rest of the way. The narrator informs you that you need the "right connections" to meet the main characters, before introducing you to the first character: Caroline, a prostitute on Church Street. Faber provides a vivid account of where she lives, where she sleeps, what she eats, and the life that led her to prostitution, leading the reader to conclude that if she is not the main character, she is at least an important supporting character. Then she meets Sugar and... goodbye, Caroline: you will hardly appear again.

If this were Les Miserables with a cast of thousands, this might not be so problematic. But just six characters take up most of the epic length, some of whom I liked far less than Caroline. Furthermore, it seems odd that Faber devotes so many pages to the horrors and degradations of Church Street when Sugar no longer lives there. At least now that Sugar has appeared, the reader will learn about her home life and be introduced to William Rackham, right?

Wrong. Just as the reader has Sugar alone, she idly passes by a carriage, and all at once, the narrative switches to William's perspective. So much for making the "right" connections for a proper introduction.

The effect is that Sugar remains mostly at arm's length for the first third of the novel -- which, given its heft, is quite a while. Maybe Faber wanted to deliver her appearances in tantalizing bits and pieces, but for me, it made that first third a tough read. A few pages of Sugar stuck between innumerable pages of Henry and Agnes.

These structural issues persist even after the first third. Faber often seems to be writing in free form, tossing out a scene because he feels like it rather than because it makes sense or builds momentum. The tour guide narrator pops up now and then, but is mostly absent until the end of the novel. Perspectives shift at random, turning characters whose thoughts you knew intimately into mysteries.

Plot. Then there is the novel's plot problem -- namely, Sugar's storyline is the only one to progress. With Agnes, it first seems as though she will have a good story arc involving struggles to overcome her ailment; but soon, Faber makes it quite clear that she will never improve. So despite some progress here and there, she mostly lapses into illness or is doped up in bed.

Yet that is substantial movement compared to Henry's subplot. Henry wants to be a clergyman, but he can't because he is in love and lust with Emmeline Fox, and at some point, they changed the rules and said that Anglican parsons couldn't marry? And he is so, so tortured about it!

Henry's dilemma would have made more sense if the Rackhams were Catholic. As it stands, a good subplot could have been carved out in which Henry finally admitted his love to Emmeline, or Henry helped Caroline, or Caroline helped Henry. Instead, Henry's subplot ends in an abrupt, crude manner without any growth or resolution.

As for Emmeline -- an intelligent, eccentric, yet respectable woman who reforms prostitutes -- she seems destined to play a major role in Sugar's storyline. Instead, she does not meet Sugar until near the end, being otherwise suspended in Henry's plot.

It is hardly a coincidence that once Henry and Agnes's chapters cease, the novel's pace picks up considerably.

Characterization. While Faber's characterization is strong enough to make you feel that certain characters deserved better, it is not without some significant holes.

The biggest of them involve William's character. William begins the novel a sad-sack, yet fun-loving fop with no head for business. Then, in less than six months, he evolves into a heavyset man consumed by business above all else. While in the first third of the novel, the reader gets his thoughts almost uninterrupted, by the end, the narrative has shifted to Sugar's point of view and William's actions are largely a mystery.

Does he love Sugar? Does he love Agnes? Why does he insist on making Agnes believe that Sophie does not exist? Would Agnes be that much worse off knowing she has a child? Does William start avoiding Sugar because he realizes that she can never take Agnes's place, or because he can't get an erection?

|

Sugar as played by Romola Garai. I pictured her more as a

ginger Uma Thurman or Hilary Swank.

|

Once Sugar moves out of Mrs. Castaway's brothel, her character and motivations become easier to understand. Even so, some of her actions draw question marks. She becomes fearful that William will start to forget her, so her answer is... to make herself available to him all the time? Because if there's one thing men hate, it's a challenge?

If Sugar were as savvy as suggested, you'd think she would realize that with people like William, less is more. If she wants him to desire her as madly as he did in the beginning, she should try to make herself less available. Instead, Sugar decides that the next step is to go from being a perfume-scented, well-dressed kept woman in a grand suite to... a dowdy governess in a cramped room upstairs.

Sugar does it in order to become indispensable to William, because at his side, there would be no limit to what she could do. But she seems to have not considered the implications of becoming William's servant. Moreover, "at his side" in what way? Most likely by becoming Mrs. Rackham after Agnes dies, but Faber never has her state it, as if fearing that it would make her less sympathetic.

So instead of a storyline where Sugar yearns to be Mrs. Rackham, only to change her mind once she gets to know Agnes, Faber has it so Sugar's ambitions are vague, and her main desires seem to be keeping William interested and learning about Agnes through her diaries (which turns out to be nothing we didn't already know). It's as if Faber had an earlier draft where Sugar had more defined ambitions, but changed it after someone complained that Sugar "wasn't very nice."

Maybe Faber would claim that he left things vague on purpose, to make the reader feel like a john who did not get everything he hoped for. But then why devote 800-plus pages to the characters at all, including multiple scenes where the same situations play out over and over? It is fine to leave some things about the characters unexpressed, but there should at least be some sense of a plan, even if that plan is very carefully hidden. Too often, it is unclear what the greater scheme is, or why characters behave the way they do.

Overall. So while Faber creates a world filled with undeniably rich sights, sounds, smells, and characters, it left me wanting. I can only imagine how much better The Crimson Petal and the White would have been if Henry and Agnes had real character arcs, or if Emmeline or Caroline were given more pivotal roles. Again, the tragedy isn't that the novel ends so abruptly, but that it wasn't better structured throughout.

Why Is the Novel Successful?

One reason for Crimson's popularity is that so many people were absorbed in the characters' lives. And while I may not feel like buying Sugar a Christmas present, I can certainly see the appeal.

That said, I suspect the novel would not have received nearly as much attention if not for one thing: Teh Sexx.

Descriptions of foreplay and sex abound in Crimson, many of them equal parts fascinating and gruesome. Nipples get twisted; semen glistens on pubic hair; one character's penis gets a rather luxurious bath. The descriptions of the consequences of sex are also there, from the prostitutes' douches to one chemical mix used to induce a miscarriage that is so horrifying, I have trouble buying that the character who used it walked away as easily as she did. (Part of me believes that after her miscarriage, she bled so heavily that she was taken to nearby St. Thomas's Hospital for a hysterectomy, and that the rest of the novel's events were part of her fever dream.)

While the novel has enough to recommend it, its status as "the book Dickens was too prudish to write" must have surely piqued countless people's interests. Come for the sex, stay for the character development. Though it worked in this case, I'm not sure it's a model that other neo-Victorian authors could follow.

That said, good characters and an intriguing premise are the only two things about Crimson that conform to the "what will sell" specifications. Otherwise, the novel thumbs its nose at conventions old and new, and is probably all the better for it.

Conclusion

So while The Crimson Petal and the White is not flawless, it is still highly readable and enjoyable. Apart from some basic elements, it is also a very different novel from my own. Well okay, in both novels, a main character has sex with prostitutes, so there's that.

Crimson is a worthy addition to the neo-Victorian genre, and if Faber ever writes the sequel that fans have clamored for, I will be among the first to order it.**

* Go read the Acknowledgements in the back if you think I'm joking.

** The Apple (2006) answers some questions, but not all.

Comments

Post a Comment