Novel Update: The Unlikeable Female Protagonist

I gave my novel draft over to be critiqued by a professional editor, as I said I would do in my last update. While she had a lot of positive things to say about the story and characters, she had one major criticism: she did not like my female protagonist.

I've gone into my novel and its characters in previous posts. Suffice it to say, my character, Isabella, has a lot of issues. She is young, angry, scared, and overwhelmed. She responds by lashing out at those who don't deserve it, with some pretty terrible consequences. As a result, she bears a life-long scar. Though she reforms, by the end of the novel, her reformation is not complete. And, to be perfectly honest, it will probably never be.

Isabella is not my first "challenging" female protagonist. For a pilot script I wrote some years ago, my female protagonist was also angry. She had just lost her job and ended a relationship. She finally bonded with her teenage niece, only to learn that that niece had been lying to her about a very important part of her life. Feeling betrayed, my protagonist ordered her niece out of her apartment. In San Francisco. At night. Even though she was the only one in the city whom her niece knew.

While my script went on to win in competition, it divided those who critiqued it beforehand. One critic felt that my female protagonist was too angry and hard, and impossible to empathize with. This was despite the fact that my female protagonist felt remorse for her actions soon afterward, looked for her niece for the rest of the night, and made up with her niece later, with no lasting harm done.

I don't know why I'm drawn to unlikeable female characters. Maybe I'm just projecting anger that I'm feeling inside. Or maybe I'm acknowledging them as human beings, that people who have been through their experiences would be that angry, and that it's more dramatically interesting to let that anger show.

Regardless, as with the protagonist in my pilot, Isabella is a divisive character. Some readers, while acknowledging that she is not the nicest person, like her and find her situation poignant. Others want someone they can root for, and believe that her unlikeable behavior brings the story down.

These negative perceptions raise several questions. Are they due to my failure to write characters, or to my being too successful? Are my characters uniquely problematic, or is it due to a larger societal prejudice against unlikeable female protagonists?

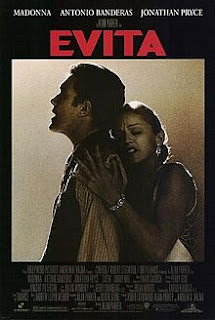

If the concern is that books starring unlikeable female protagonists won't sell, it should be put to rest. Books with unlikeable female protagonists have sold a lot of copies. A lot of copies. For every Elizabeth Bennett, there is an Emma Woodhouse. For every Jane Eyre, there is a Catherine Earnshaw.* And then there is the grande dame of unlikeable female protagonists: Scarlett O'Hara.

Given Scarlett O'Hara's nature, why would anyone want to read about her for 1,000 pages? It's not because she has a tragic backstory: although slightly distant from her mother, she is spoiled by both of her parents and wants for nothing at the beginning of Gone With the Wind. She has strength and resiliency, but it's for her own survival, which by default helps other members of her family. She loves just one person throughout, while hating or resenting everyone else, including her sisters and her children. She causes the death or ruin of more than one good-hearted character.** And finally, she yearns for a world that few people today would revere: one where slavery was reinstated and those "darkies" knew their place.

Yet people do read about her quite willingly, myself included. For me, there's something about Scarlett that, even long after her antics have grown tiresome, feels satisfying and alive. And maybe to some people, many people, that's enough.

Nonetheless, there does seem to be a larger societal prejudice against "unlikeable" women, not just in fiction, but in general. With this prejudice comes, it seems, a basic dislike of complexity. Many people would say that they like "strong" women. Yet when "strong" is defined, the woman ends up sounding more like an archetype than a flesh-and-blood human being. She should be confident. She should be aware. She should know what she wants. She should take actions that express what she wants. What she wants should be admirable and, most importantly, not the slightest bit inconvenient to others, unless those others come from a group that is obviously in the wrong and must be defeated.

Both real and fictional women who fail to meet all of the "strong" requirements get criticized for what they supposedly lack. Hillary Clinton, Yoko Ono, Empress Alexandra of Russia... the list goes on and on. Women who don't meet any of the requirements are not even worth considering. If, by chance, a fictional female character does take unpopular actions while also being "strong," she saves herself only if she is fully aware of her wickedness, embraces it, and is willing to face the consequences. "I don't care if she's a bitch, as long as she owns it," is a lament that I've read more than once about nasty female characters. Yet how many real people, let alone fictional women, act in such a black-and-white manner?

While men and male characters face these expectations, it is not to the same extent as women and female characters. Readers and viewers have also been exposed to a wider range of male characters over the centuries. By contrast, in much of the mainstream media, complex female protagonists who display qualities other than "strong" and virtuous are still a rarity, but are gradually becoming more acceptable.

As for why many people shy away from characters who are not easy reads, who zig when you expect them to zag, who knows. Essays have and will be written about readers' character preferences. Maybe readers who dislike complicated characters believe that if they are making such an investment of time, they should know what they are getting. I expressed in my Fingersmith review that I disliked Maud's change in Part Two. Though that wasn't so much about her becoming more complicated as it was her becoming flatter and less interesting, at least in my view. But I digress.

Where does that leave Isabella, my female protagonist? In many ways, she displays "strong" qualities, such as having to make decisions on behalf of a large household, or making decisions that frighten her as she tries to learn who betrayed her mother. At the same time, her most fateful decision is made without her knowing why she's made it until afterward. We then learn that it was based in fear and insecurity. While to some readers, it might be nothing more than a wrinkle in her character, to others, it could wreak of a serious betrayal.

As for whether I'll soften her at all, I haven't decided. If there is one thing I've learned, everyone has opinions, and some are greatly divergent. Even if I soften her character, someone will be dissatisfied, whether it's because she's still too "hard" or because she's too soft. Right now, I like her the way she is -- unlikeable and all.

* Granted, Cathy isn't exactly a protagonist so much as one main character in Wuthering Heights, but still, her complete awfulness hasn't discouraged new readers.

** Her second husband, Frank Kennedy, died after attacking freedmen as part of a Ku Klux Klan raid, but the novel portrays it as a noble effort to avenge Scarlett, who had been threatened earlier.

The above image was used under the Fair Use Doctrine.

Comments

Post a Comment