Downton Abbey: Does Nostalgia for Our Own Country's Greatness Make It Popular in the United States?

While I sit here in the United States waiting for Downton Abbey's Series Four -- not at all reading episode spoilers or looking for places to download the episodes -- I have been thinking about the show's appeal to Americans. Part of it is no doubt due to the fascination with British history, its aristocracy, and the pretty-pretty that comes with it. But another reason could be the nostalgia for our country's past.

Not that everything was so great in the U.S. from 1912 to 1922. After World War I, there were greater tendencies toward xenophobia and isolationism. "Lost Generation" writers like Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald rejected post-war American culture. Life was still significantly worse for anyone who was not a white male of Anglo-Saxon descent.

Yet at the same time, the U.S. was taking center stage for the first time. Woodrow Wilson introduced the idea of the League of Nations, which was unsuccessful, but paved the way for the United Nations. The U.S. economy had already become the world's largest economy in 1880, thanks to a combination of natural resources and innovation. On the social front, democracy was being expanded, with the passing of the Seventeenth Amendment (direct election of U.S. Senators), and the Nineteenth Amendment (women's right to vote).

While not everything was perfect, it is easy to look back and see the U.S. from the late 19th century through World War II as an up-and-comer, a rising power in the world, whose best days still lay ahead. Its people started small, but through natural scrappiness and innovation, rose to the top. While American money could be credited with saving decadent old institutions like the British aristocracy, Americans in no way absorbed their decaying values.

Look no further than Downton Abbey's treatment of Martha Levinson for this stereotype. Sure Martha is stinking rich, but she's still a plain-spoken American who says what she thinks when she thinks it, and is more practical than social minded. While the British may scorn her, she (or at least her money) really provides what they need. There is the sense that if the Crawleys adopted a little more of Martha's attitude, they would be better off in the long run.

Never mind that the stereotype of the plain-spoken, scrappy American doesn't entirely hold up. Edith Wharton's novels alone could tell you that Americans were just as capable of becoming decadent and narrow-minded as their European brethren. In fact, if anything, "new money" families like the Levinsons might have been even gaudier and more wasteful in their effort to prove they belonged.

While Horacio Alger values were preached, the late 19th Century and early 20th Century saw a steep rise in inequality. Families like the Vanderbilts and the Astors were hardly "just folks" as they built their palaces at Newport Beach and on Fifth Avenue.

At the same time, Americans can look at the greater arc of history and say, "Well yes, but the Progressive Era fixed that, and World War II..." The overwhelming view of the U.S. back then is a young country a bit rough around the edges, but clearly on the upward swing.

Compare that with now. Though less than 100 years older, the U.S. feels old, tired, and a bit overstretched. There is widespread inequality, but seemingly no relief in sight. The economy has been sluggish, and a right-wing faction in government refuses any attempt to stimulate it. Once the "savior" who rolled in to the rescue in world conflicts, the U.S. faces complicated messes in the Middle East with no easy resolution. Seemingly every week, new reports come out proclaiming which year China will have the world's biggest economy.

One can still look at the big picture and feel optimistic, but without knowing what comes next, it is difficult. Whereas we can look back both smugly and with longing at the early 20th Century, glossing over its worst traits, classifying its harsh events and views as "quaint." Just like the events in Downton Abbey -- real, divisive events come across like slightly frayed edges on an ornate tapestry. Yes, equality matters, but not as much as which spoon goes with what dish, and whether to wear a white waist coat.

That is why we watch -- to feel nostalgic, and perhaps to feel reassured. People back then thought that the world was ending, but we know that it didn't. Both British and Americans -- even with their grandiose views of Empire and Manifest Destiny -- probably never thought that people would look back upon them fondly decades later. As difficult as it is to believe, one day people may look back at our time, gloss over the government shut downs and the NSA spying, and see us as a golden era.

We can only hope.

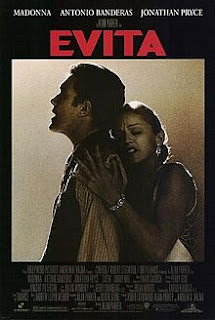

The above photo is being used under the Fair Use Doctrine.

Not that everything was so great in the U.S. from 1912 to 1922. After World War I, there were greater tendencies toward xenophobia and isolationism. "Lost Generation" writers like Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald rejected post-war American culture. Life was still significantly worse for anyone who was not a white male of Anglo-Saxon descent.

Yet at the same time, the U.S. was taking center stage for the first time. Woodrow Wilson introduced the idea of the League of Nations, which was unsuccessful, but paved the way for the United Nations. The U.S. economy had already become the world's largest economy in 1880, thanks to a combination of natural resources and innovation. On the social front, democracy was being expanded, with the passing of the Seventeenth Amendment (direct election of U.S. Senators), and the Nineteenth Amendment (women's right to vote).

While not everything was perfect, it is easy to look back and see the U.S. from the late 19th century through World War II as an up-and-comer, a rising power in the world, whose best days still lay ahead. Its people started small, but through natural scrappiness and innovation, rose to the top. While American money could be credited with saving decadent old institutions like the British aristocracy, Americans in no way absorbed their decaying values.

Look no further than Downton Abbey's treatment of Martha Levinson for this stereotype. Sure Martha is stinking rich, but she's still a plain-spoken American who says what she thinks when she thinks it, and is more practical than social minded. While the British may scorn her, she (or at least her money) really provides what they need. There is the sense that if the Crawleys adopted a little more of Martha's attitude, they would be better off in the long run.

Never mind that the stereotype of the plain-spoken, scrappy American doesn't entirely hold up. Edith Wharton's novels alone could tell you that Americans were just as capable of becoming decadent and narrow-minded as their European brethren. In fact, if anything, "new money" families like the Levinsons might have been even gaudier and more wasteful in their effort to prove they belonged.

While Horacio Alger values were preached, the late 19th Century and early 20th Century saw a steep rise in inequality. Families like the Vanderbilts and the Astors were hardly "just folks" as they built their palaces at Newport Beach and on Fifth Avenue.

At the same time, Americans can look at the greater arc of history and say, "Well yes, but the Progressive Era fixed that, and World War II..." The overwhelming view of the U.S. back then is a young country a bit rough around the edges, but clearly on the upward swing.

Compare that with now. Though less than 100 years older, the U.S. feels old, tired, and a bit overstretched. There is widespread inequality, but seemingly no relief in sight. The economy has been sluggish, and a right-wing faction in government refuses any attempt to stimulate it. Once the "savior" who rolled in to the rescue in world conflicts, the U.S. faces complicated messes in the Middle East with no easy resolution. Seemingly every week, new reports come out proclaiming which year China will have the world's biggest economy.

One can still look at the big picture and feel optimistic, but without knowing what comes next, it is difficult. Whereas we can look back both smugly and with longing at the early 20th Century, glossing over its worst traits, classifying its harsh events and views as "quaint." Just like the events in Downton Abbey -- real, divisive events come across like slightly frayed edges on an ornate tapestry. Yes, equality matters, but not as much as which spoon goes with what dish, and whether to wear a white waist coat.

That is why we watch -- to feel nostalgic, and perhaps to feel reassured. People back then thought that the world was ending, but we know that it didn't. Both British and Americans -- even with their grandiose views of Empire and Manifest Destiny -- probably never thought that people would look back upon them fondly decades later. As difficult as it is to believe, one day people may look back at our time, gloss over the government shut downs and the NSA spying, and see us as a golden era.

We can only hope.

The above photo is being used under the Fair Use Doctrine.

Comments

Post a Comment